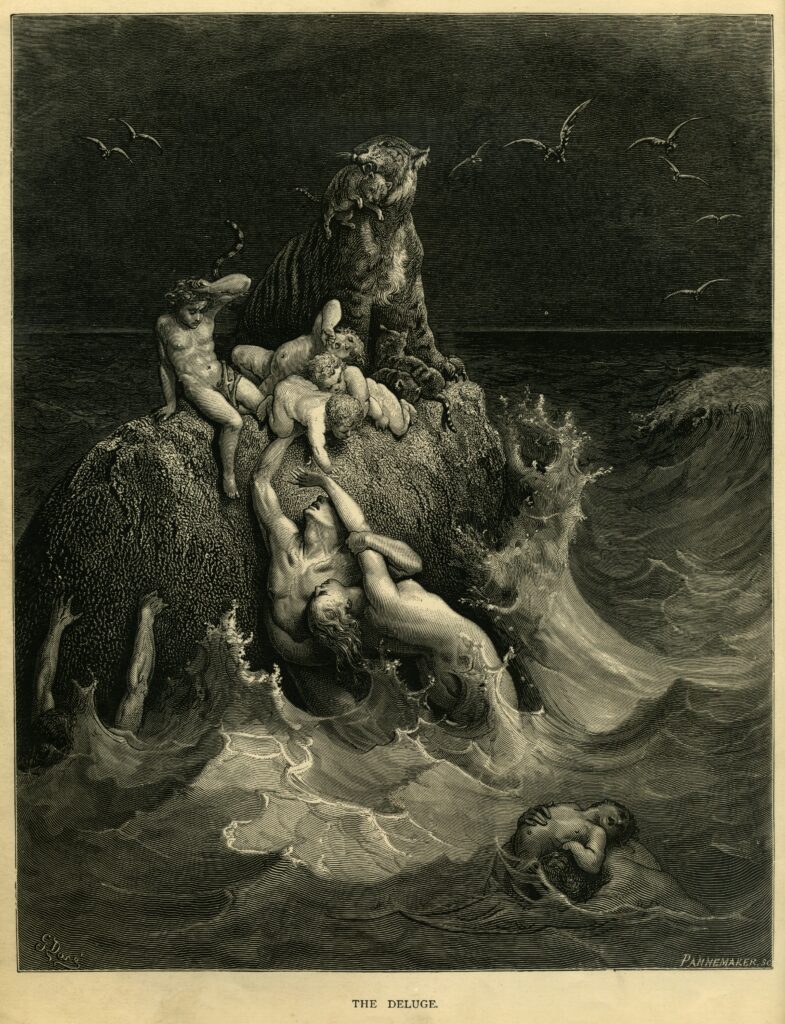

Flood myths appear across human history as a common theme in ancient cultures separated by vast distances. Recorded as early as 3000 BC in Mesopotamia, these accounts also surface in oral traditions from the Americas. They describe massive floods tied to divine action or natural upheaval. Scholars debate whether they reflect actual events, cultural exchanges, or universal ideas. Thus, this pattern across continents raises questions about origins and significance that remain unresolved.

Early Records of Deluge

Flood myths first emerge in Mesopotamia on tablets dated around 3000 BC. The Epic of Gilgamesh details Utnapishtim constructing a boat on Ea’s command to survive a six-day flood. By 1700 BC, Sumerian records mention Ziusudra enduring a deluge sent by Enlil to eliminate human faults. These narratives establish a framework of divine judgment and survival.

This motif extends beyond Mesopotamia to other regions with distinct versions. In Greece, around 1200 BC, Deucalion and Pyrrha escape Zeus’ flood in a chest and reach Mount Parnassus. India’s Matsya Purana, from ~1000 BC, describes Manu tying his boat to a fish during Vishnu’s deluge. China’s Yu the Great, from 2070 BC legends, manages a flood by redirecting rivers, showing a recurring focus on water’s power.

Variations Across Continents

The Americas feature flood myths with similar descriptions despite geographic divides. The Hopi in Arizona recount a flood destroying a corrupt world, with Spider Woman aiding survivors to safety. Meanwhile, the Inca’s Unu Pachakuti, preserved in ~500 AD oral tales, spares two people atop an Andean peak during a deluge. Polynesian traditions tell of Maui raising islands after a flood, a narrative handed down through generations.

Africa contributes its own examples, like the Yoruba of Nigeria recalling Olokun’s ocean overtaking villages until Ifa ensures survival. Egypt’s Nun, from 3100 BC records, presents floodwaters as a creative force rather than destruction. Yet most versions share a pattern: divine floods reshape the earth, leaving a few to rebuild, prompting questions about a shared source or parallel development.

Ties to Natural Events

What explains these flood myths? Some researchers connect them to documented floods in ancient regions. Mesopotamia’s Tigris and Euphrates rivers flooded Sumerian lands by 3000 BC, potentially inspiring Gilgamesh’s tale. India’s Indus Valley saw monsoon surges around 2000 BC, possibly influencing Manu’s story. Coastal Polynesians faced tsunamis that altered landscapes, which could account for their flood lore.

However, timelines don’t always match—Greece’s floods differ from Sumer’s—so a single event seems unlikely. Climate data suggests Ice Age melts around 12,000 BC raised sea levels by 400 feet, flooding shores. This might have seeded early memories, though evidence remains indirect. The diversity of timing and detail complicates a unified natural origin.

Patterns of Purpose

Flood myths often serve purposes beyond recounting events, embedding cultural values in their structure. In Gilgamesh, gods target human flaws, testing Utnapishtim’s merit through survival. Deucalion’s stone-throwing rebirth and Manu’s rescue by a fish highlight renewal and virtue. Yu’s flood control reflects order over chaos in Chinese tradition. Thus, these accounts function as moral lessons, not just historical notes.

Ritual reinforces this role—Mesopotamian priests linked floods to divine intent, shaping offerings to appease gods. The Hopi saw floods as cycles of world renewal, guiding their practices. Egypt’s Nun framed water as creation’s start, distinct yet tied to purpose. So, these myths shaped belief systems across varied societies.

Persistence Through Time

Flood myths persist beyond their origins, adapting across cultures with lasting impact. The Bible’s Noah, documented in ~1200 BC texts, mirrors Gilgamesh with an ark and animals surviving a deluge. India’s Manu influences Hindu cycles, while Polynesian Maui’s island-raising endures in oral chants. The Yoruba’s Olokun remains central to Nigerian rites, showing water’s enduring significance.

This longevity reaches modern contexts—flood narratives still resonate in stories and studies worldwide. After thousands of years, these myths maintain relevance, connecting past beliefs to present curiosity about their roots.

Transmission Across Borders

How did flood myths spread so widely? Oral traditions likely carried them as tribes migrated—Mesopotamian tales could have reached Greece via trade. Sumerian goods, like beads, hit Egypt by 3000 BC, possibly with stories attached. Yet the Hopi and Inca versions suggest independent origins, as no direct links bridge the Pacific.

Their forms vary—tablets in Sumer, chants in Polynesia—but the core holds: floods erase, survivors rebuild. This consistency implies either widespread exchange or a common human response to water’s force. Either way, the telling itself became a craft that outlived its makers.

Unanswered Threads

The lack of a single explanation keeps flood myths a subject of debate—no unified flood ties them all. Sumerian rivers don’t align with Hopi highlands; Greek arks differ from Chinese channels. Were they local floods or Ice Age echoes? Since no definitive records clarify this, their origins stay uncertain.

Now spanning global cultures, flood myths persist as a thread through history’s fabric. After 5,000 years, they remain a puzzle—too varied to pin down precisely, too old to dismiss entirely. Each account invites analysis of a past too broad for simple answers.