Few finds in Egyptology rival the unveiling of a pharaoh’s resting place, and the Thutmose II tomb stands as a landmark discovery. Announced on February 18, 2025, by a British-Egyptian team, this burial site near Luxor marks the first royal tomb uncovered since Howard Carter’s 1922 breakthrough with Tutankhamun. Located west of the Valley of the Kings in the Theban Hills, it dates to around 1479 BC, when Thutmose II ruled as the fourth king of the 18th Dynasty. Yet its empty chambers and flood-worn state raise more questions than answers about his reign and final rest.

A Hidden Chamber Found

The Thutmose II tomb emerged after years of patient digging, with its entrance first spotted in October 2022. The team, led by Piers Litherland, initially thought it housed a royal wife due to its spot near Hatshepsut’s tomb and those of Thutmose III’s consorts. Months of clearing flood debris—a mix of limestone and mud—revealed a different truth. A steep staircase and wide corridor led to a chamber with a blue ceiling flecked with yellow stars, a hallmark of pharaohs’ burials.

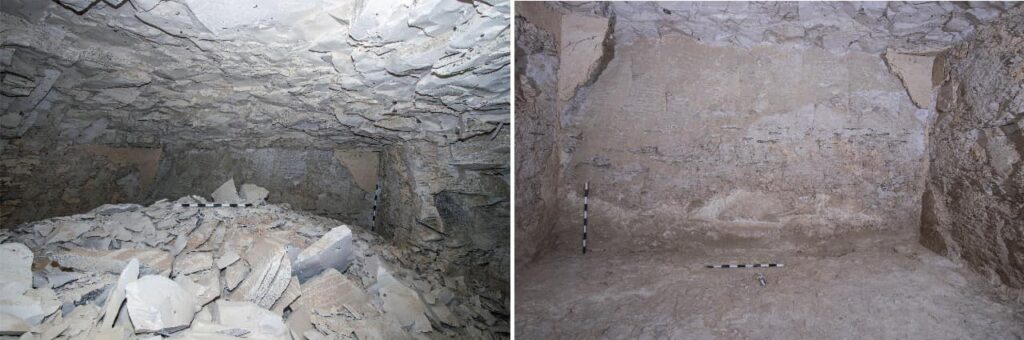

Inside, broken alabaster jars bore inscriptions naming Thutmose II and his wife, Hatshepsut, tying the site to him beyond doubt. The chamber stretched deep, its walls once lined with plaster, though now cracked and bare. No mummy or treasures filled it; ancient floods had swept through soon after burial, leaving only fragments. That emptiness sets it apart from Tutankhamun’s gilded hoard, yet its discovery still echoes as a rare window into Egypt’s 18th Dynasty.

A King’s Brief Rule

Thutmose II took the throne around 1493 BC, son of Thutmose I and Mutnofret, a lesser wife. His reign, lasting perhaps 13 years or as few as three, ended around 1479 BC at age 30. Married to his half-sister Hatshepsut—daughter of Thutmose I and Queen Ahmose—he fathered a son, Thutmose III, who later ruled as a famed warrior. Yet Thutmose II himself left a lighter mark, known for modest campaigns against Nubian rebels and Bedouin tribes in Sinai.

Hatshepsut, though, shaped his legacy. After his death, she ruled as regent for Thutmose III, then claimed the throne herself, becoming one of Egypt’s few female pharaohs. The Thutmose II tomb hints at her hand—its alabaster inscriptions credit her with his burial, a detail that suggests she oversaw its making or moving. Her own tomb lies in the Valley of the Kings, raising questions about why his rests apart.

A Flooded Fate

Unlike Tutankhamun’s intact chambers, the Thutmose II tomb tells a tale of ruin. Built beneath a waterfall’s path in Wadi Gabbanat el-Qurud, it faced flooding soon after burial—perhaps within six years. Water poured through, smashing grave goods and forcing priests to act. They likely moved his mummy and treasures elsewhere, leaving broken jars and plaster scraps behind. That second site, possibly under a nearby rubble mound, remains unfound.

The tomb’s layout reflects early 18th Dynasty style—a grand staircase, a sloping passage, and a single burial room. Faint scenes from the Amduat, a sacred text for kings, cling to the walls, though flood scars mar them. Its poor state contrasts with later Valley of the Kings tombs, richer and better shielded. Yet that very damage offers clues to ancient choices—why build here, and where did they take him next?

A Wife’s Decision

Why place the Thutmose II tomb outside the Valley of the Kings? At his death, that valley wasn’t yet the standard royal graveyard—Thutmose I had begun it, but habits shifted later. Hatshepsut’s role adds a twist. She started a tomb 1,640 feet away, abandoned when she took power and moved to the valley as pharaoh. Some argue Thutmose II picked this spot himself, while others see her steering his burial to this western wadi, perhaps for safety or status.

Her influence looms large. The inscriptions call her “god’s wife” and “great chief wife,” titles she held before ruling. Did she choose this site to honor him apart from her future glory? Or did flood risks go unseen? The Thutmose II tomb sits near other royal women’s graves, hinting at a family cluster before the valley took hold—a shift she helped cement.

Echoes of a Lost Reign

The discovery stirred Egyptology in 2025, ending a drought since Tutankhamun’s find. Though empty, it’s the first 18th Dynasty king’s tomb located since then—others, like Psusennes I’s in 1940, lie outside this dynasty or area. Fragments of jars and plaster offer the first grave goods tied to Thutmose II, whose mummy surfaced in 1881 at Deir el-Bahari, moved there centuries after looting. That relocation ties to the flood, a practical act now fueling hope for a second, intact site.

Locals and visitors near Luxor feel its pull too. Rangers at the Theban Necropolis limit access, but the tale spreads—a king lost, then found. It reshapes his story, often overshadowed by Hatshepsut’s reign and Thutmose III’s wars. His modest rule, once a footnote, now gains weight with this physical trace.

Unsettled Queries

The Thutmose II tomb leaves gaps. Why build under a waterfall—poor planning or unseen risk? Where’s the second site—beneath that 75-foot rubble pile nearby? Experts eye it, but digging lags due to safety fears. Did Hatshepsut shift him to shield his rest, or was it haste? No records say; the 18th Dynasty kept few diaries.

After 3,500 years, it stands near Luxor, a cracked shell of a king’s end. The Thutmose II tomb doesn’t match Tutankhamun’s splendor, yet it challenges Egypt’s timeline. Was he a quiet ruler or a lost key to his dynasty’s rise? Each shard hints at answers still buried.