Around 360 BC, Greek philosopher Plato introduced the Lost City of Atlantis in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias, describing a grand island civilization that sank beneath the sea 9,000 years earlier, around 9600 BC. Written as a cautionary tale, his account placed this advanced society beyond the Pillars of Hercules, often tied to the Strait of Gibraltar. Since then, scholars and explorers have debated its existence, with no definitive archaeological evidence emerging. Today, the Lost City of Atlantis persists as a captivating blend of ancient narrative and unanswered question, nudging us to explore its roots in fact, fiction, or something in between.

The Lost City of Atlantis in Plato’s Vision

In 360 BC, Plato penned Timaeus and Critias, crafting a story of the Lost City of Atlantis as a vast island larger than Libya and Asia combined, per translations from the University of Athens. Over decades, he outlined its concentric rings of water and land, governed by ten kings descended from Poseidon, thriving until greed triggered its downfall around 9600 BC. For centuries, his dialogues served as moral lessons, not chronicles, though he claimed the tale came from Egyptian priests via Solon. Could it echo a real catastrophe? Consequently, Plato’s vivid details launched a quest that endures today.

Echoes in Ancient Ruins

Since 360 BC, searchers have linked the Lost City of Atlantis to real-world sites, often citing Mediterranean disasters, per studies from the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Around 1600 BC, the Santorini eruption sank parts of Thera, a Minoan hub with advanced structures, echoing Plato’s tale, though its date mismatches 9600 BC, per University of Arizona radiocarbon data. Meanwhile, Pavlopetri off Greece, submerged by 3000 BC, offers another parallel with its urban layout. Could these events have shaped his story? For now, no site fully aligns with his timeline or scale, keeping the search open.

Theories Across Seas and Sands

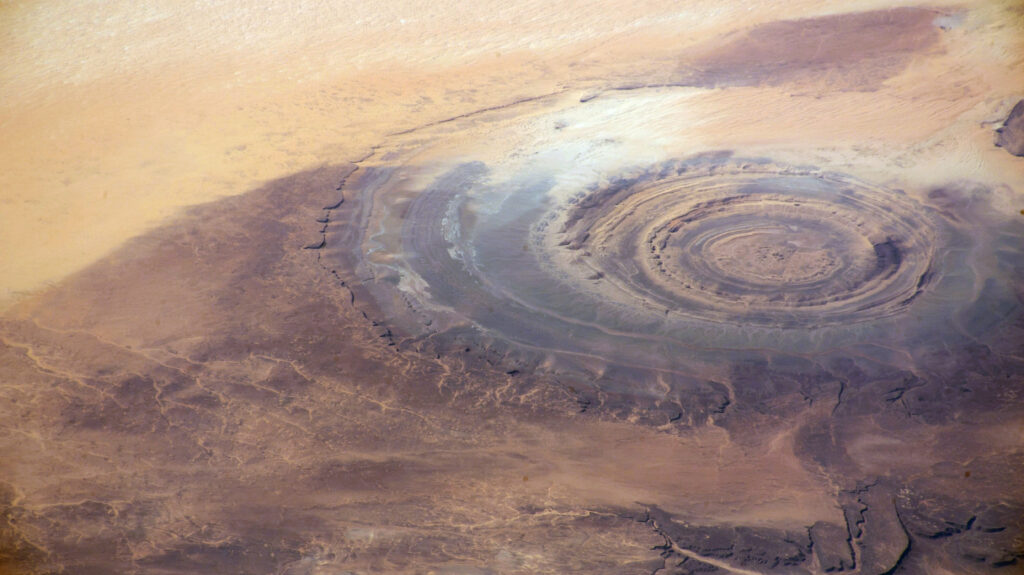

Over time, ideas about the Lost City of Atlantis have spanned continents, blending myth with possibility. Some, like historian Richard Ellis, argue Plato invented it as a parable, per his 1998 AD book Imagining Atlantis. Others point to the Caribbean’s Bimini Road, found in 1968 AD as underwater stones, though deemed natural limestone by University of Miami geologists. Alternatively, the Richat Structure in Mauritania, a 25-mile-wide concentric formation visible since 1965 AD satellite imagery from NASA, matches Plato’s rings, with some suggesting a coastal flooding around 9600 BC, per geological surveys. Thus, each theory fuels debate without a clear victor.

Atlantis in Modern Curiosity

Now a global fascination, Lost City of Atlantis drives expeditions and media, its story housed in texts like those at the British Museum. Beyond its legend, it spurs digs like Santorini’s 2023 AD efforts by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, seeking Minoan ties without Atlantis proof. Since Plato’s era, it has shaped our view of vanished worlds, from scholarly quests to wild claims. Ultimately, this ancient island remains a lingering riddle, urging us to sift history for its spark of truth.