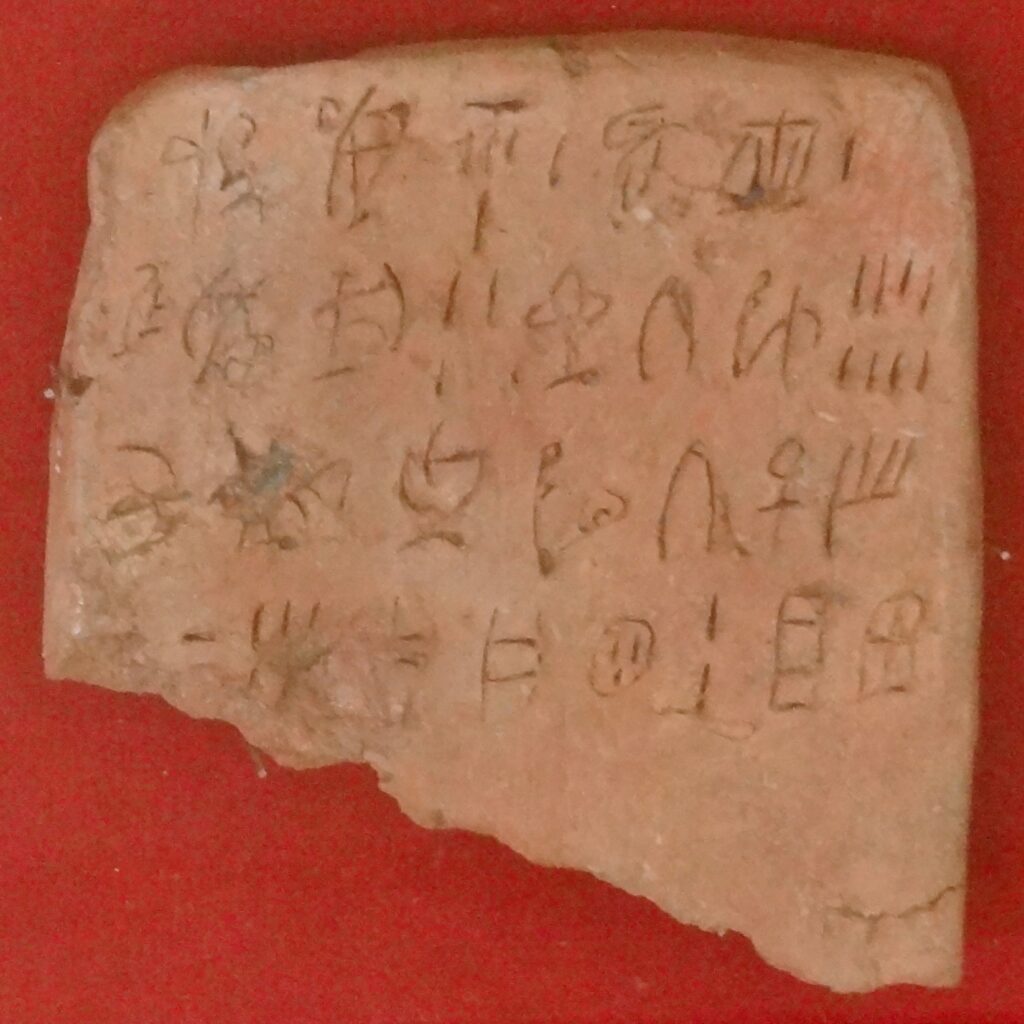

On Crete and nearby Greek islands, Linear A stands as one of Europe’s oldest scripts, etched into clay tablets, seals, and pottery by the Minoan civilization between 1800 BC and 1450 BC. Discovered in 1900 AD by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans during excavations at Knossos, this writing system features over 90 distinct signs, from simple lines to complex shapes like eyes and tools. Since then, Linear A has resisted decipherment, unlike its successor Linear B, decoded in 1952 AD as early Greek. Today, Linear A remains a captivating challenge, offering a glimpse into Minoan life while guarding its secrets from modern eyes.

Linear A’s Discovery at Knossos

In 1900 AD, Evans unearthed Linear A tablets at Knossos, a sprawling Minoan palace on Crete, revealing a script distinct from Egypt’s hieroglyphs, per his findings published by Oxford University Press. Over months, he cataloged hundreds of clay fragments inscribed with this system, dating them to 1800 BC to 1450 BC through stratigraphy at the site, later refined by the University of Oxford. For centuries, these tablets lay buried, their symbols intact due to Crete’s dry climate. Could they hold records of Minoan trade or rituals? Consequently, this find opened a window into a lost world, sparking a century of study.

Writing a Minoan Legacy

Between 1800 BC and 1450 BC, Minoans scratched Linear A into clay with styluses, creating a syllabic script of 90-plus signs, per analysis from the University of Cambridge. Around this time, they used it across Crete and islands like Santorini, marking goods and tablets with symbols for numbers and goods like wheat or oil, as found in Akrotiri digs by Spyridon Marinatos in 1967 AD. Unlike Linear B, which records Mycenaean Greek, Linear A’s language eludes us, though some signs match B’s, per Michael Ventris’s 1952 AD work. Meanwhile, its complexity hints at a skilled society. For now, its undeciphered words preserve Minoan voices in silence.

Clues to an Unknown Tongue

Since 1900 AD, Linear A has defied translation, with scholars like John Chadwick suggesting it records a non-Greek language, possibly linked to pre-Indo-European tongues, per his 1970 AD book The Decipherment of Linear B. Over decades, attempts to crack it using Linear B’s key failed, as only 10% of signs align, per University of Bristol studies. Could it be a lost Minoan dialect tied to trade across the Aegean? Alternatively, some propose a ritual code, though no bilingual tablets—like the Rosetta Stone—have surfaced, per digs at Phaistos since 1908 AD by Federico Halbherr. Thus, its meaning stays just out of reach.

A Script’s Lasting Echo

Now held in museums like Heraklion’s Archaeological Museum, Linear A draws linguists and visitors, its tablets a window into Minoan Crete, per ongoing studies by the University of Crete. Beyond its clay, it reflects a culture flourishing from 1800 BC to 1450 BC, with 2023 AD scans by the British School at Athens revealing new sign variants. Since Evans’s time, it has fueled quests to unlock Europe’s ancient past. Ultimately, Linear A endures as a quiet challenge, urging us to hear a voice lost to history.