Across Laos’ Xiangkhoang Plateau, the Plain of Jars scatters a riddle in stone—an array of vessels hinting at an ancient culture’s past. Found in clusters from one to hundreds, these relics stretch over hills and valleys, marking a presence in northern Laos. Dated to around 1240 BC, they stand as silent traces of a people lost to time. Were they tombs, storage urns, or something else? This question keeps the Plain of Jars a focus for study and curiosity.

A Field of Silent Giants

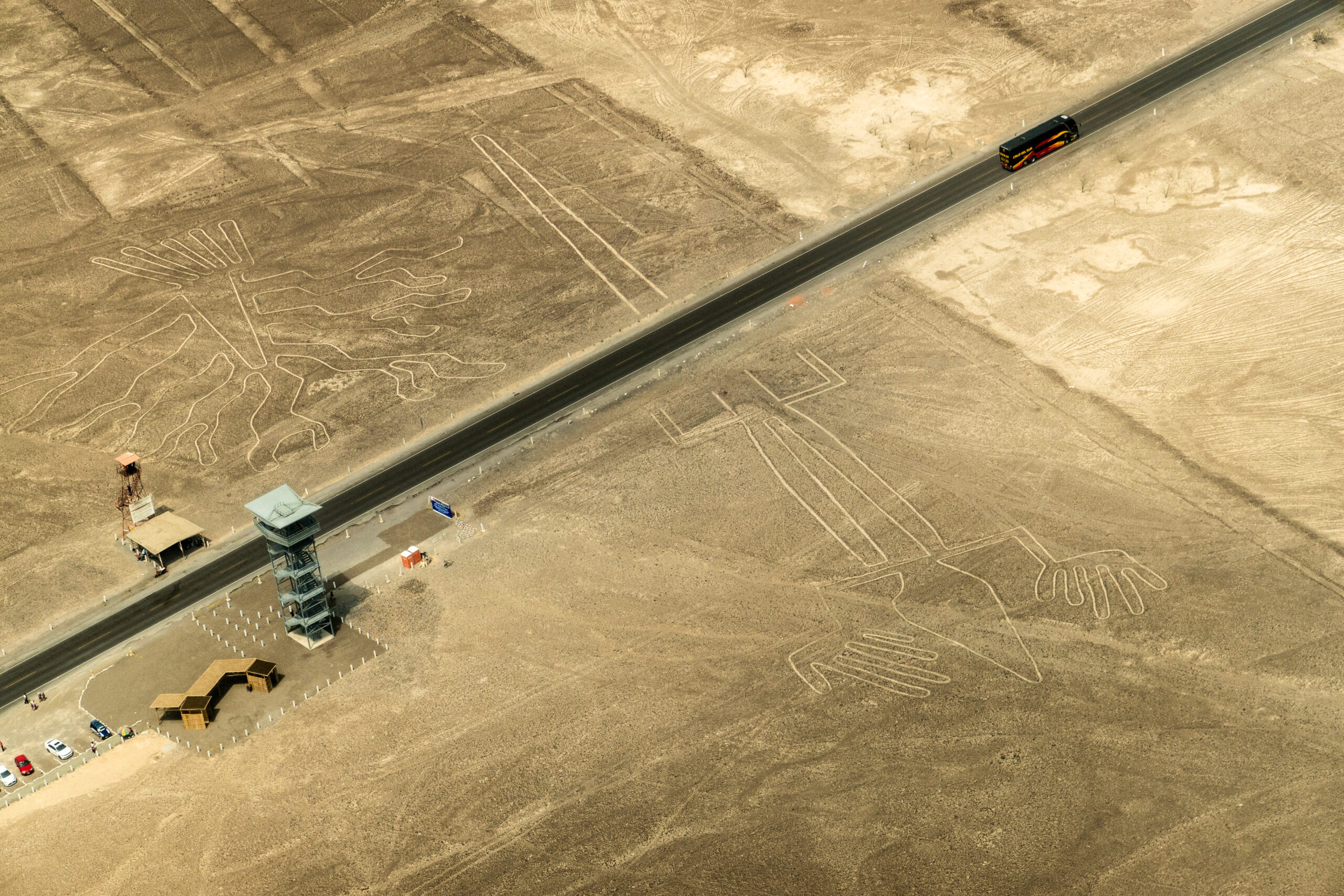

The Plain of Jars first drew notice in the 1930s when French explorers mapped its expanse near Phonsavan, a town 250 miles northeast of Vientiane. Workers clearing land later found more, pushing the tally to over 90 sites with thousands of jars. Crafted from sandstone, granite, and limestone, they range from three to ten feet tall and weigh up to 14 tons each. Most sit upright with rims hinting at lost lids, while a few bear carvings—one etched with a frog-like figure stands apart.

Their spread covers rugged terrain, from low foothills to upland slopes and open plains. Some sites hold a lone jar, while others cluster 400 strong. Erosion and war have toppled many, yet their bulk endures Laos’ tropical rains and winds. That resilience suggests a purpose beyond mere decoration, a lasting mark of intent from a people who shaped them over 3,200 years ago.

A People Without a Name

The jars date to 1240 to 660 BC, rooted in the Iron Age of Southeast Asia. Charcoal and soil tests fix this range, tying them to a group that thrived before written records began. These folk likely used iron tools, carving stone from quarries miles away—some five miles distant—and hauling it across rough land. Pottery shards, beads, and bronze bits near the jars point to a skilled society, perhaps enriched by trade along routes linking China, Vietnam, and beyond.

Their lives took shape on this plateau, a high plain at the Annamese Cordillera’s edge. They grew rice, fished rivers, and hunted game in forests now vanished. Cairns and stone circles dot the area too, showing a knack for lasting landmarks. The Plain of Jars fits this pattern, a crafted trace of a culture that faded without leaving its name.

Tools of Death or Life?

What drove their making? Most agree the Plain of Jars served burial rites. Ash, burnt bones, and clay urns near some jars suggest cremation—bodies burned, then gathered for burial. The big vessels might have held remains during decay, a step before final rest, akin to later Thai and Khmer royal customs. Smaller jars nearby, capped with stone discs, held cleaned bones, marking a second burial phase.

Other ideas persist, though. Locals recall tales of giants brewing rice wine in these urns to celebrate a war’s end—a king’s victory toast. Another view sees them as water tanks for traders crossing dry plains, collecting monsoon rains. Beads and tools inside bolster this trade link, yet no food traces remain. While each theory offers insight, the cremation evidence leans strongest toward a purpose tied to death.

Cut from Stone

The jars’ craft impresses even now. Hewn from sandstone blocks or riverbed boulders, they took shape with iron chisels over weeks or months. Their cylindrical forms flare at the base, some tapering to a lipped rim—an edge for lids now lost to rot or theft. Sizes vary; one at Site 1 near Phonsavan tops ten feet and weighs tons, a giant among its kin. Most lack marks, but rare carvings—like that frog—hint at skilled hands beyond basic cutting.

Quarries dot the plateau, some miles from the jar fields, showing the haul these makers faced. Workers shaped each piece onsite or dragged rough blocks to their spots—tough work in Laos’ heat and hills. That effort underscores a goal bigger than storage; the jars’ size and spread suggest a lasting mark, not a quick fix for daily needs.

A Landscape Interrupted

The Plain of Jars endured time but not war unscathed. During the 1960s and ‘70s, U.S. bombings in the Vietnam War era left scars—craters pock the plateau, and unexploded bombs linger near Site 1. Locals adapted, using some jars as shelters or troughs, while others cracked under blasts. Cleanup since the ‘90s cleared paths, yet risks remain—only three sites welcome visitors safely.

That past shapes its present. Tourists tread Site 1’s cleared trails, peering into jars amid bomb pits, while Sites 2 and 3 offer quieter views. UNESCO aids preservation, listing it in 2019, but war’s toll limits digs. The jars’ bulk holds firm despite this, a testament to their makers’ skill and a land’s hard history.

A Wider Echo

This find reframes Laos’ early story. By 1240 BC, Southeast Asia saw iron spread—tools, not just bronze—yet the Plain of Jars shows a mix of old and new. Stone urns echo Vietnam’s Dong Son urns, while trade beads tie to Thailand’s Ban Chiang sites. Did these folk trade with neighbors or hold their own ways? No metal tools surfaced here, suggesting a slower shift from stone.

The plateau’s perch hints at links too. Sitting high, it caught trade winds across the Annamese range, a crossroads for rice and flint. The Plain of Jars might mark a hub—or a sacred zone—bridging local life with wider tides. Its scale and spread argue for a group with means, not a lone clan’s whim.

Unsettled Clues

The Plain of Jars leaves questions open. Were all for burial, or some for water? Ash ties most to cremation, yet no full graves clarify it. Why so many—thousands—across 90 sites? No texts explain since this culture left only stone. Did war or time hide more clues? Laos’ bombs and rains keep some answers buried.

Now, it spans Xiangkhoang’s hills, a quiet field of stone giants. After 3,200 years, the Plain of Jars holds steady, a burial puzzle unsolved. Its weathered urns whisper of a past too deep to grasp fully, urging patience for what’s still unseen.