The Nazca Lines stretch across Peru’s arid coastal plain, forming a vast gallery of ancient geoglyphs unlike any other. Carved between 500 BC and 500 AD, these figures cover hundreds of square miles near Nazca city. Thus, they reveal a people who thrived in a harsh desert setting. Animals, plants, and geometric shapes emerge from the sand. Were they water markers, star maps, or ritual paths? This question continues to intrigue scholars and travelers alike.

Shapes Above the Sands

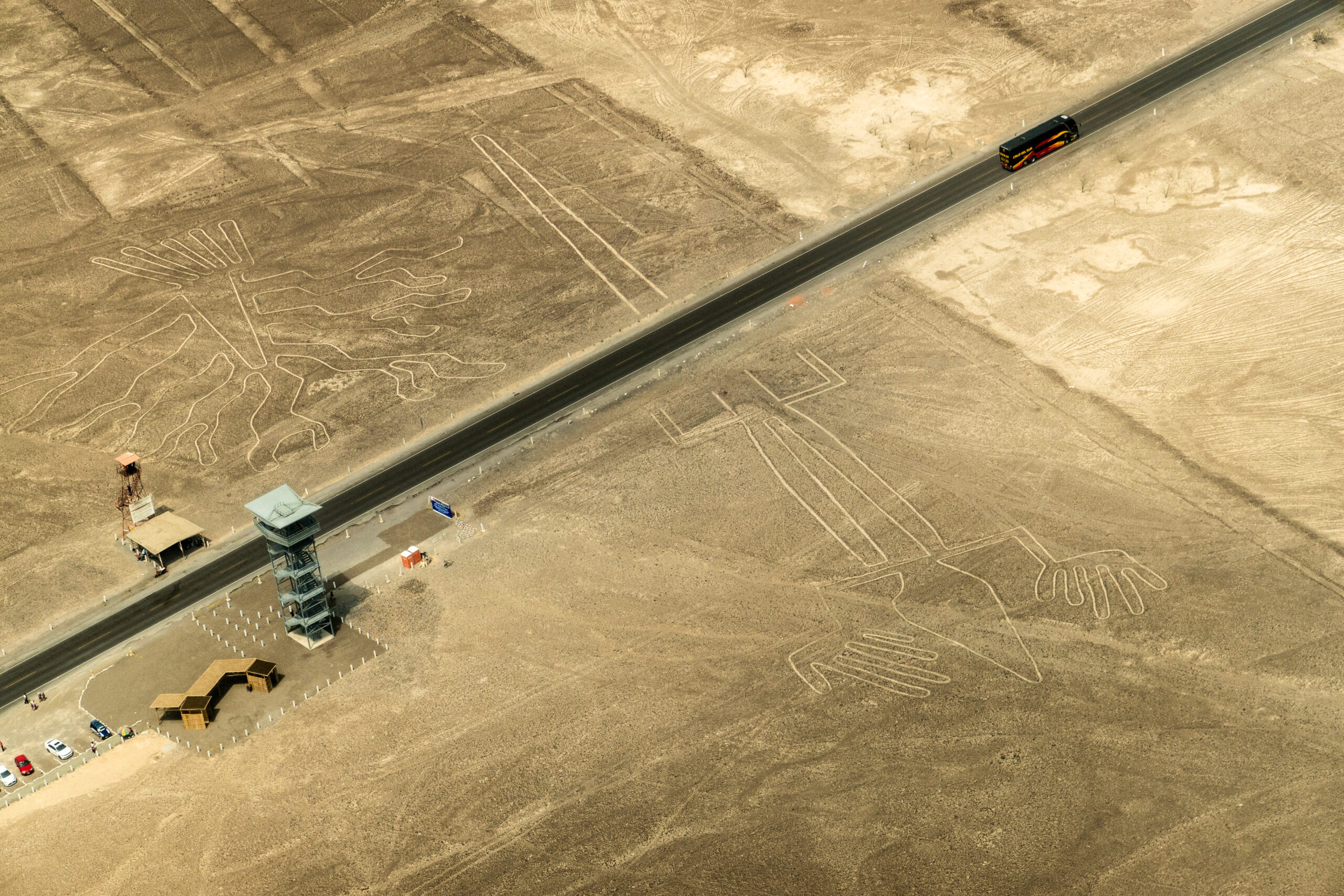

Pilots first noticed the Nazca Lines in the 1920s while flying over Peru’s desert, spotting figures unseen from the ground below. In 1927, Peruvian archaeologist Toribio Mejía Xesspe traced lines that extended up to 30 miles across the landscape. By the 1930s, aerial surveys unveiled over 70 shapes, including hummingbirds and condors, plus countless spirals. These geoglyphs span from 50 to over 1,000 feet in width.

Their impressive scale persists today because dry air, with less than an inch of rain yearly, preserves them well. However, their size kept them hidden until aircraft rose high enough to see. This combination of craft and seclusion underscores the Nazca Lines as a testament to ancient ingenuity.

People of the Parched Plain

The Nazca culture, active from 100 BC to 800 AD, crafted these geoglyphs along Peru’s southern coast. They farmed in a dry land, using irrigation channels to tap underground streams for crops. Also, they produced vivid pottery and tightly woven cloth with skilled hands. Thus, the Nazca Lines mirror their ability to shape a challenging environment.

They settled near Cahuachi, a ritual center roughly 20 miles from the lines they etched. Burials there, wrapped in fine textiles, often included trepanned skulls cut for healing or rites. This blend of craft and tradition defines their time, yet the lines remain their boldest legacy, begun around 500 BC.

Purpose in the Patterns

Why did they carve such shapes? Some suggest the Nazca Lines guided water in a desert where rain rarely falls. Straight lines could point to aquifers or rivers, vital in a dry region. Hummingbirds and spiders, linked to rain in Andean lore, support this theory as pleas to gods like Kon. Yet few wells align with these paths, casting doubt on the idea.

Alternatively, Maria Reiche saw them as star charts when she mapped them in 1941, noting ties to Orion’s Belt. Critics argue that stars shift over time, though, weakening her case. Another view posits priests walked the lines in rituals, honoring deities across the sand like later Inca trails.

Nazca Lines Drawn with Precision

Creating the Nazca Lines required steady effort with wooden stakes and stone tools. Workers scraped off dark, iron-rich pebbles to reveal pale soil beneath, forming a sharp contrast. Lines stretch two inches deep and up to 20 feet wide across the desert floor. Figures like the monkey and whale demonstrate planning, adapting to hills without losing their shape.

Teams worked for years under a blistering sun, moving rocks aside without wheels or animals. The desert’s hard crust preserved their efforts since wind and rare rain barely touch it. That precision links to the Paracas Candelabra, a glyph 180 miles northwest, reflecting similar ancient coastal artistry.

Seen from the Skies

The lines remained unseen until planes soared above in the 1930s, revealing their vast scale to pilots. Locals knew some paths, but only air surveys showed the full picture by 1941. UNESCO later named them a World Heritage Site in 1994 for their uniqueness. Today, tourists board flights from Nazca’s airstrip to see them clearly.

That aerial view unveils their craft—condors span 400 feet, astronauts stand 100 feet tall on slopes. Straight lines reach miles, often aimed at hills or stars, though their spread stays hidden from ground level. This sky-bound perspective remains key to grasping their design.

Traces of a Faded Culture

The Nazca Lines mark a culture that faded by 800 AD, likely due to drought or conflict. Cahuachi’s adobe mounds fell, irrigation dried up, and their glyphs endured as a final sign. Beyond Peru, the Paracas Candelabra, carved 200 miles away around 200 BC, shares a similar riddle of purpose. That tie suggests a coastal craft lineage, perhaps borrowed or evolved.

Maria Reiche’s 50-year study built their fame, while digs uncovered pottery and bones nearby. Modern scans reveal more lines today, yet their role remains unclear. This silent craft outlasts its creators, a testament to their lasting mark.

Questions Still Buried

No texts survive to explain the Nazca Lines since the Nazca left none behind. Were they for water, stars, or rites—or a mix of these aims? Drought hid clues, and burials offer no tools to clarify. Also, modern tracks fade some lines, a loss to growth over time.

Now stretching across Peru’s desert, they form a vast sketch on arid ground. After 2,500 years, the Nazca Lines hold steady, a puzzle carved in silence. Each shape poses questions no dig has resolved, pushing us to probe a past too wide to fully grasp.