Among the ruins of Hattusa, the ancient capital of the Hittite Empire in central Turkey, Hattusa’s green stone stands out as a striking and unexplained artifact. Located in the Great Temple of this Bronze Age city near modern Boğazkale, this polished nephrite block measures roughly 27 inches per side and weighs about 2,200 pounds. Dating back to at least 2000 BC, its smooth, cubic form contrasts with the surrounding limestone remnants, marking it as a unique feature of a once-powerful civilization. Scholars debate its purpose—altar, statue base, or ritual object—while locals call it a “wish stone,” adding layers of intrigue to its history that persist thousands of years later.

Emergence in an Ancient Capital

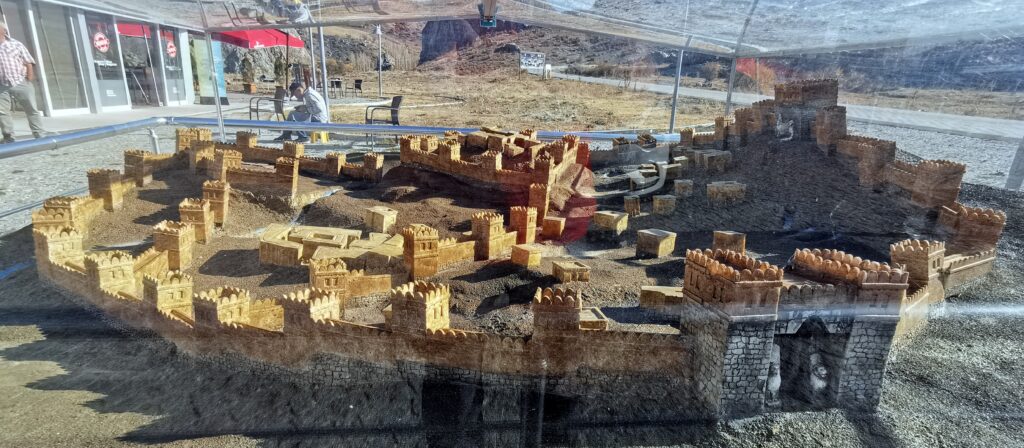

Hattusa’s green stone resides within the Great Temple, a key structure in the Hittite capital established by 2000 BC. The city, sprawling across 440 acres in Çorum Province, served as the empire’s heart from around 1650 BC until its collapse near 1200 BC. German excavations beginning in 1906 uncovered this nephrite block in a storeroom near the temple’s southern entrance, alongside cuneiform tablets and ceremonial relics. Unlike the region’s common limestone, its distinct green hue and polished finish suggest deliberate crafting, not natural placement.

The Hittites settled Hattusa around 2000 BC, building atop a site occupied since the 6th millennium BC. They expanded it into a fortified hub with massive walls and over 30 temples, yet no texts mention this stone. Its discovery amid the temple’s rubble, preserved by chance, raises questions about its role in a city razed by fire around 1700 BC and rebuilt thereafter. That lack of documentation fuels speculation, as Hattusa’s green stone defies simple explanation.

A Civilization of Stone and Power

The Hittites, who rose to prominence in Anatolia by 1650 BC, crafted Hattusa’s green stone during their early ascendancy. They controlled a vast empire stretching from modern Turkey to northern Syria, rivaling Egypt and Babylon. Known for advanced metallurgy and diplomacy, such as the 1274 BC Kadesh treaty with Egypt, they built Hattusa with limestone quarried nearby, shaping temples and palaces atop a high plateau. Yet nephrite, a form of jade, isn’t local; its nearest sources lie in the Taurus Mountains, over 300 miles south, or even farther in Europe.

Their society blended trade and conquest, managing resources with cuneiform records on clay. Hattusa’s green stone, however, stands apart—no similar blocks appear in Hittite sites, hinting at a special function. Its placement in the Great Temple, a 215-by-140-foot complex likely dedicated to the Sun-goddess Arinna and Storm-god Tarḫunna, suggests a link to their pantheon of thousands. Yet its isolation among the ruins leaves its makers’ intent unclear, a silent relic of a culture lost to time.

Features of an Unusual Block

Hattusa’s green stone measures approximately 27 inches per side, forming a near-perfect cube, a shape rare in Hittite architecture. Weighing around 2,200 pounds, its nephrite composition contrasts with the softer limestone of Hattusa’s walls and bases. Polished to a smooth finish, it reflects light faintly, suggesting hours of grinding with tools like sandstone or quartz, a labor-intensive process for Bronze Age artisans. No carvings or inscriptions mark its surface, unlike the reliefs of lions and sphinxes on nearby gates.

Its location in a temple storeroom near the southern street adds to its oddity; other ritual items, like altars or statue bases, sit in open courts. That isolation prompts theories: was it moved post-collapse, or placed there intentionally? Nephrite’s durability resists weathering, yet its purpose—altar, throne, or base—remains speculative. This lack of parallels in Hittite finds keeps it a standout anomaly, a crafted object with no clear match.

Theories on Purpose and Origin

What role did Hattusa’s green stone play? Scholars offer several possibilities based on its context and form. Its temple setting suggests a religious function, perhaps an altar for offerings or a base for a deity’s statue, common in Hittite worship. The cube’s shape and polish imply significance, possibly a focal point for rituals tied to Arinna or Tarḫunna. Yet its storeroom placement counters this; altars typically stood in public view, not tucked away.

Another theory posits it as a diplomatic gift; some suggest Egypt’s Ramesses II sent it post-Kadesh, though nephrite isn’t native there either. Its distant source fuels trade hypotheses; Hittites imported tin and lapis lazuli from afar, so nephrite from the Taurus or beyond isn’t implausible. However, no records support this, and its uniqueness among Hittite artifacts challenges gift ideas. Locals’ “wish stone” label adds a folk angle—centuries of touch have worn it smooth—but offers no archaeological clue.

Preservation Amid Collapse

Hattusa’s green stone survived thanks to the city’s fate; fire around 1700 BC and abandonment by 1200 BC buried it in rubble. The Great Temple, hit by flames that baked clay tablets, shielded the stone under debris until German digs in 1906. Unlike wood or softer stone, nephrite withstood time; its storeroom’s collapse entombed it, safe from looters who stripped gates and walls. Today, it sits exposed near Boğazkale, a UNESCO site since 1986.

That durability contrasts with Hattusa’s ruin; earthquakes and erosion hit other temples, yet this block held firm. Preservation efforts now guard it; tourists touch it, but rangers limit damage. Its survival offers a rare glimpse into Hittite priorities, though its isolation hints it outlasted its use.

A Global Echo in Stone

Hattusa’s green stone fits a wider Bronze Age pattern of worked stone objects across cultures. Egypt’s obelisks and Greece’s baetyls from ~2000 BC share polished finishes, though nephrite remains rare outside East Asia. Hittite trade stretched to Babylon, making distant sourcing feasible—tin came from Afghanistan, lapis from Badakhshan. Yet its singularity—no twin stones at Hattusa or nearby Yazılıkaya—keeps it distinct, an anomaly without a clear parallel.

Beyond Turkey, it draws researchers; 3D scans in 2023 mapped its wear, yet its role stays vague. Its nephrite form and temple context suggest a cultural marker, but its isolation defies broader trends. That uniqueness fuels its status as a Bronze Age question.

Questions Unresolved

Why does Hattusa’s green stone endure as a mystery? No Hittite tablets name it; cuneiform lists grain, not nephrite, leaving purpose blank. Was it sacred, symbolic, or utilitarian? Its storeroom spot suggests storage, not display, yet its craft implies intent. Did invaders like the Kaskians shift it, or Hittites hide it during collapse? Time obscures these answers since 1700 BC fires silenced its makers.

Now in Boğazkale’s ruins, Hattusa’s green stone stands firm after 4,000 years. This nephrite block persists, too distinct to dismiss, prompting analysis of a Hittite past too deep to fully resolve.