Across Mexico’s Gulf Coast lowlands, the Colossal Olmec heads loom as enduring symbols of an ancient Mesoamerican civilization, showcasing remarkable skill from over 3,000 years ago. Crafted between 1400 and 900 BC by the Olmec people, these massive basalt sculptures, 17 known today, stand up to 11 feet tall and weigh as much as 50 tons each. Moreover, they were discovered starting in 1862, featuring distinct facial traits and helmets, thus sparking debate over their purpose and the identities they depict. Consequently, the Colossal Olmec heads remain a cornerstone of Olmec archaeology, offering insights into a culture that shaped early Mesoamerica while leaving questions unanswered.

Origins Amid Gulf Coast Ruins

The Colossal Olmec heads trace back to the Olmec heartland, spanning modern Veracruz and Tabasco, where San Lorenzo and La Venta thrived as key centers by 1400 BC. For example, farmers found the first head in 1862 at Tres Zapotes, followed by San Lorenzo’s ten in 1945 and La Venta’s four by 1958, excavations led by Matthew Stirling and Alfonso Caso. Each site yielded heads carved from basalt, a volcanic rock quarried 50 to 60 miles away in the Tuxtla Mountains. Furthermore, radiocarbon dating of nearby charcoal places their creation between 1400 and 900 BC, marking the Olmec’s Formative Period peak.

These sites sat in swampy lowlands fed by rivers, ripe for maize but distant from stone sources, suggesting a robust transport system. Yet no Olmec records explain their making because the civilization left no deciphered script, unlike later Maya. That absence fuels analysis of how and why these heads emerged, tied to a people who vanished by 400 BC.

The Olmec: Pioneers of Stone

The Olmec thrived from ~1500 to 400 BC, crafting the Colossal Olmec heads during their cultural and economic rise. They farmed maize, beans, and squash in fertile floodplains, fished rivers, and traded jade and obsidian across Mesoamerica; routes stretched to Oaxaca and Guatemala. Known as the region’s “mother culture,” they built San Lorenzo with earthen mounds by 1200 BC, later shifting to La Venta’s pyramid complexes.

Their society mixed farming with hierarchy; consequently, elites likely oversaw labor for monuments like the heads. Tools of flint and chert shaped basalt, a craft refined over generations. Thus, the Colossal Olmec heads reflect this power since their scale and detail suggest a civilization with resources and organization, yet their decline—marked by site abandonment, remains unclear, leaving their artistry as a primary legacy.

Features of Monumental Sculpture

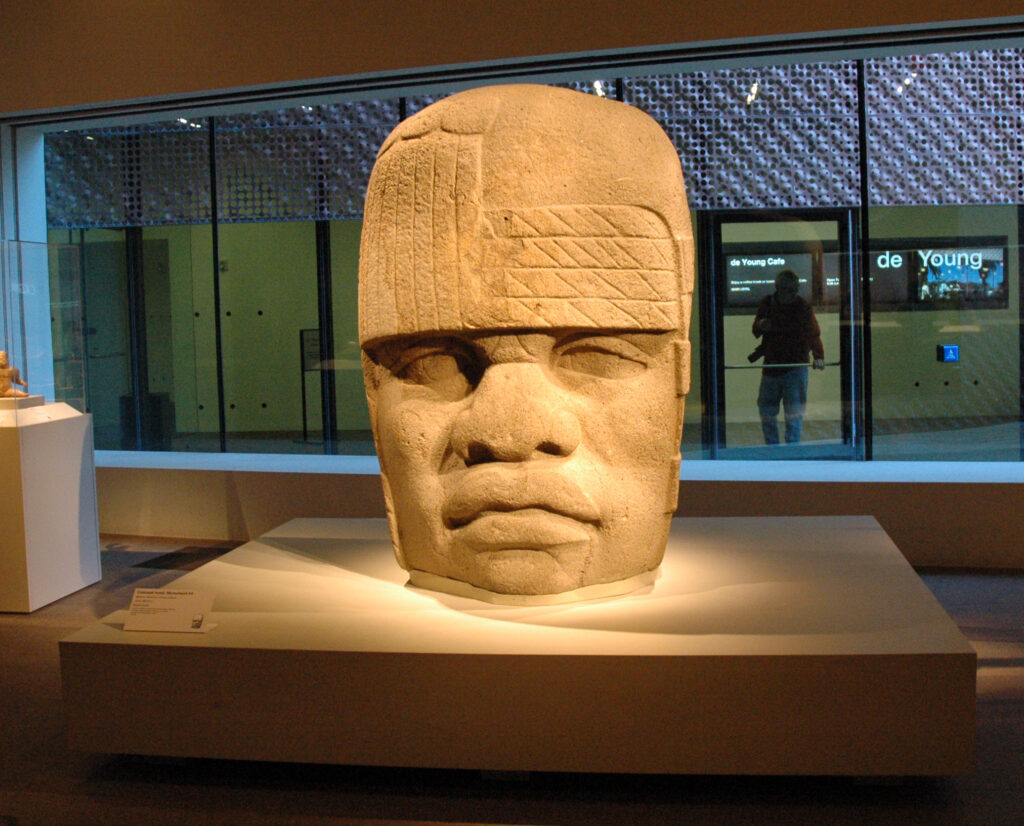

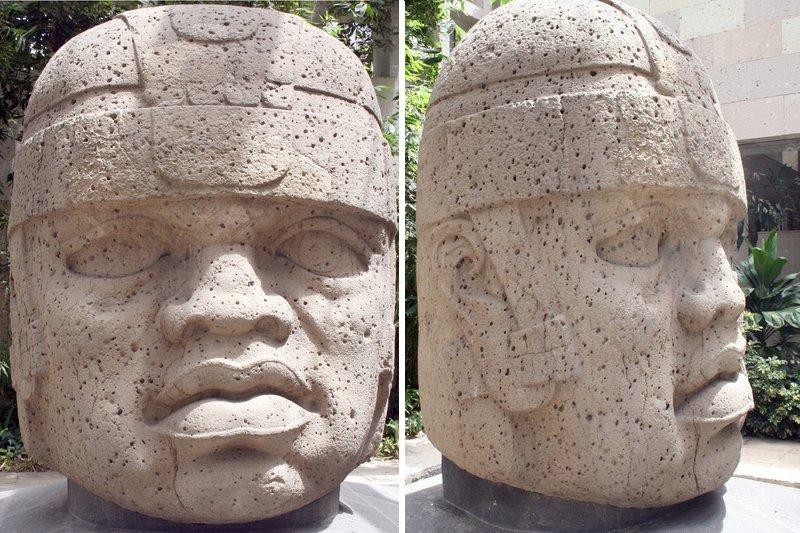

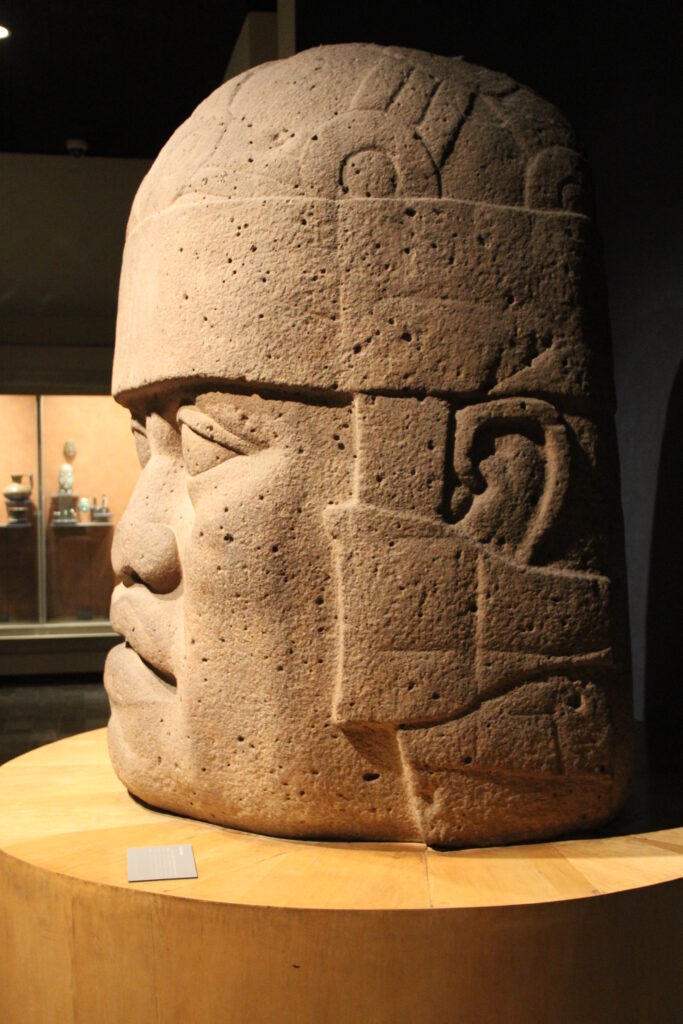

The Colossal Olmec heads range from 4 to 11 feet tall, each weighing 6 to 50 tons, carved from single basalt boulders. Their faces show broad noses, thick lips, and downturned mouths—unique traits per head—topped by tight helmets with straps or earflaps. For instance, San Lorenzo Head 1, at 9.4 feet, wears a patterned cap, while La Venta’s Monument 1, 8 feet, has a plain helm. No two match exactly, hinting at individual portraits rather than generic forms.

Their detail stands out; polished surfaces gleam, and eyes with nostrils show precision, yet purpose eludes. Were they rulers, deities, or ancestors? Basalt’s durability preserved them because they were buried by 900 BC, resisting erosion in damp soil. That craftsmanship marks a leap since few Mesoamerican works rival their size or realism from this era.

Crafting Giants from Basalt

Making the Colossal Olmec heads demanded skill and logistics beyond basic tools. Workers quarried basalt from Cerro Cintepec, 50 miles from San Lorenzo, splitting boulders with fire and stone wedges. Transport relied on rafts down rivers like the Coatzacoalcos; 50-ton loads then moved over swampy trails and rolled on logs to sites. Flint chisels and abrasives shaped each head, a process taking months per piece; estimates suggest 1,500 worker-days for one.

That effort reflects Olmec capacity; thus, hundreds hauled stone, and dozens carved it under humid skies. No metal aided—just stone and grit—but the heads’ polish rivals later works. Their burial, possibly ritual, hid them by 900 BC, preserving them for modern finds. This scale suggests a society with surplus and structure, though no texts detail the feat.

Unearthed in Modern Times

The Colossal Olmec heads surfaced in 1862 when farmer José Melgar spotted Tres Zapotes Head 1 in a hacienda field; locals knew it as a buried “pot.” Stirling’s 1945 digs at San Lorenzo uncovered ten more, mapped via aerial surveys, followed by Caso’s La Venta work adding four by 1958. Carbon dating of ash and soil pegged their age—1200 BC for San Lorenzo’s peak, tying them to Olmec decline by 900 BC.

Museums now hold most; for example, Veracruz’s anthropology hub guards seven, yet threats linger. Looting hit Tres Zapotes in the 1900s, while erosion wears La Venta’s exposed stones. That rediscovery shifted views since the Olmec predated Maya, reshaping Mesoamerican timelines—however, their heads’ full story stays buried.

A Wider Mesoamerican Frame

The Colossal Olmec heads fit a Mesoamerican arc; Zapotec stelae (500 BC) and Maya statues (300 AD) echo their scale, though basalt use sets them apart. Olmec trade stretched jade to Costa Rica by 1000 BC, suggesting influence; consequently, Teotihuacan’s later pyramids owe them a debt. Yet no Olmec script survives—unlike Maya glyphs, leaving their heads a mute marker of a pioneer culture.

Beyond Mexico, they draw study; 3D scans in 2023 map wear, and tourists hit San Lorenzo yearly. Their realism and size hint at a shift—portraiture before writing—but their isolation from Olmec tools or texts keeps them distinct, a cultural anchor without a clear root.

Questions Still in Stone

No Olmec records name the Colossal Olmec heads’ purpose, was it rulership, worship, or memory? Faces differ, San Lorenzo’s ten vary in lips and helms, but no clues say why. Did war or drought bury them by 900 BC? Erosion hides more, yet La Venta’s swamp holds undug finds. That silence—400 BC collapse left no trace; fuels debate over a culture too old for full answers.

Now scattered across museums and ruins, the Colossal Olmec heads stand firm after 3,000 years. This basalt legacy persists—too grand to ignore, linking us to an Olmec world too deep to fully resolve.